As uptake of weight-loss jabs soar, our Nature and Land-use Programme Manager asks what they could mean for Britain's food, farming and environment.

The meteoric rise of weight loss drugs has reignited debates about personal responsibility, inequality, and the role of the state in shaping health.

Labour’s Health Secretary, Wes Streeting, has embraced them as part of his 10 Year Health Plan for England: seen as crucial to easing NHS pressures and in helping people get back to work. The government expects to expand rollout to 3.4 million people over the next decade, alongside a much larger private market. With obesity estimated to cost the UK £126 billion each year, and leaving many individuals living with chronic disease, the political appeal is clear. In the USA, recent data suggests the growing use of weight loss drugs may already be reversing obesity trends for the first time in years.

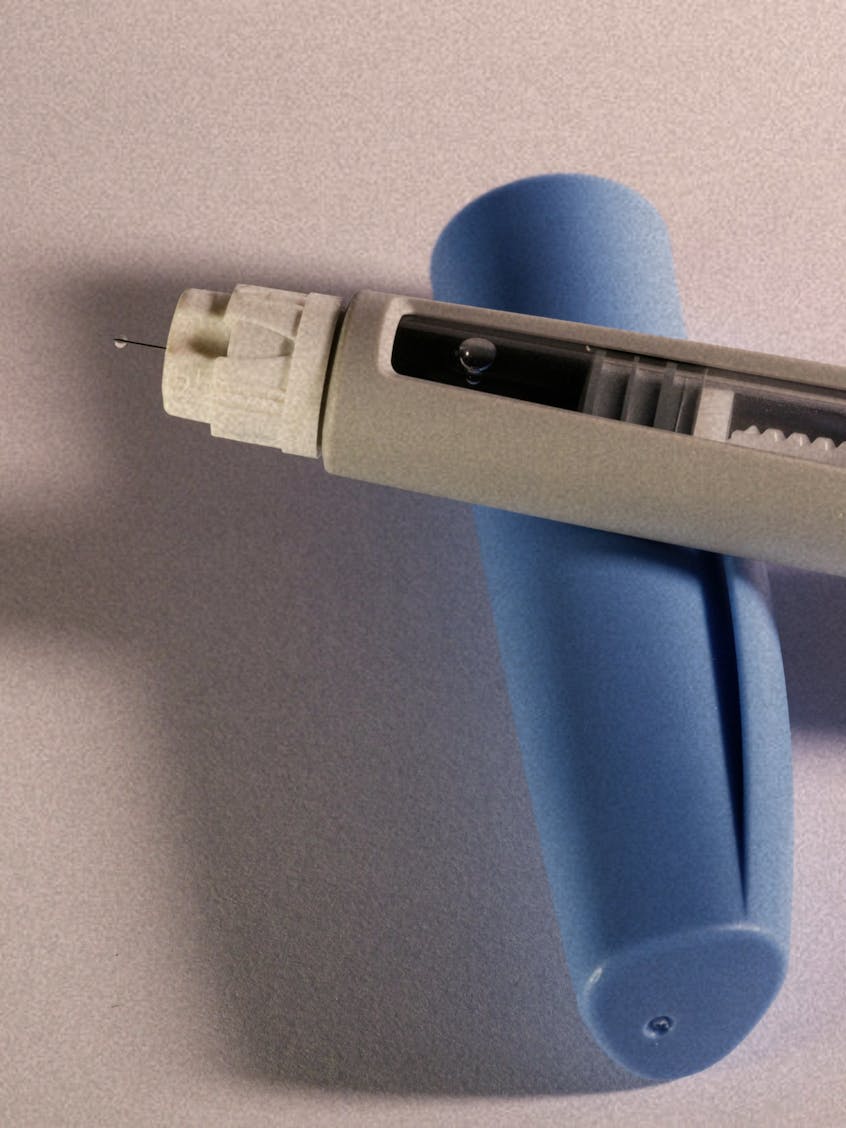

The numbers are already eyewatering. Over 1.5 million people in the UK are using the drugs, mostly privately. Streeting recently claimed that ‘half’ of his colleagues are on them. As patents expire, and pill-forms arrive – likely within a year - costs will plummet. Newer drugs already carry fewer side effects and dozens more are coming. Within a decade tens of millions in the UK, and many more worldwide, could be using them.

Both supporters and critics abound, but Streeting is poised to drive a revolution in how we treat obesity – and a host of other conditions. And one potential consequence has barely entered the conversation: what happens to our farming and environment when millions of people start eating differently?

Appetite for change

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic mimic a hormone that tells the body it’s full. The result is that people eat and snack less - often 700 - 900 fewer calories each day. That’s up to 45% of the daily recommended calorie intake for women in the UK. Many lose 15–20% of their body weight within months.

It's not just less food, people change what they eat too: fewer sugary drinks and refined grains, more fruit, vegetables, and lean protein. Many cut back on red meat and dairy in favour of poultry or legumes. Remarkably, GLP-1 drugs also appear to significantly reduce cravings for nicotine and alcohol.

From health revolution to farming transition?

If uptake keeps surging – and all signs indicate it will – the environmental ripples will be huge. Our farming sector feeds Britain, but it also covers 69% of our land and has – through decades of intensification - become a primary driver of biodiversity loss. Our food system contributes up to 38% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions.

If the UK’s 19 million obese adults cut 700 calories a day, it would be equivalent to roughly 6.3 million fewer loaves of bread – and almost half a million fewer acres of farmland required each year. That’s nearly twice the land used to grow potatoes and more than triple that for vegetables.

What we grow could change too. Reduced appetite for refined sugars, carbohydrates and oils would mean we grow fewer commodity crops like wheat, oilseeds and sugar beet and more fibre-rich legumes, fruits and vegetables.

The food industry is already adapting. The question remains whether British farmers will too. Diversifying production and finding new routes to markets can improve the resilience and profitability of farm businesses, but the pace of change will create both winners and losers. Globally, billions changing what they eat will hit food markets and prices in unpredictable ways.

Some environmentalists see this as a rare opportunity. Lower demand could free land for other uses - restoring nature at scale would grow our carbon sinks, create more green spaces for the public and can protect homes from flooding downstream. Farmers could shift practices to be less intensive and more nature-friendly, using fewer pesticides and chemical fertilisers. More diverse crop rotations could bring benefits to soil health and improve the resilience to droughts and flooding. Emissions from farming, transport and processing would all drop.

Breaking the ‘Junk Food Cycle’

None of this is inevitable. A reshape for farming will only happen alongside effective government policy. Moreover, to shift demand at the scale required weight-loss drugs will first need to break what Defra calls the “junk food cycle” - the feedback loop between our appetite for ultra-processed, sugar- and fat-laden products, and the commercial incentives to supply them.

Campaigners have spent decades trying to bend that cycle - pushing sugar taxes, advertising bans, and reformulation targets - but often lost to industry lobbying. It is just possible that GLP-1 drugs could sidestep the politics entirely - forcing the food industry to follow changing appetites. Portion sizes are already shrinking. Sugary snacks are competing with protein-fortified ones. The question is now whether “Big Food” will now attempt to bypass the effects of the drug's effects entirely.

The point of no return

Streeting’s public embrace of weight loss drugs is turbocharging demand. Pharmacies are already running short. Barring a major health scare they will become a routine part of personal health care for many within a few years.

They are no magic bullet yet. They work best with expensive support services that help people navigate their weight loss journey safely. People often regain weight when they stop. The long-term health effects are still uncertain, and at £120–£300 a month, they remain out of reach for most who might benefit.

But here’s the remarkable thing: one of the biggest levers on British farming and the environment may now not sit in Defra, but in the Department for Health. The surge in GLP-1 use is driving the biggest shake-up of our food system in decades. The food industry’s response, and ours in turn, will determine what we grow, how we farm, and what our landscapes look like. The change is already in motion - and we won’t have to wait long to see where it leads.